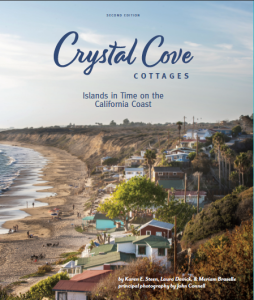

From Crystal Cove Cottages: Islands in Time on the California Coast

On an August evening sometime in the mid-1950s, as another perfect Southern California day drew down to darkness, a small sailboat on its way home to the Newport Beach harbor skated too close to shore and found itself trapped in the surf. The sailors were starting to panic when a group of browned and burly men on the shore spotted them and swam out through the black water to help beach the boat. As they landed, the smell of roasting meat wafted over from what looked to be a village of thatched huts set amongst palm trees and tropical growth. On the beach, a group of natives sat around a bonfire, drinking and singing. Behind this cozy enclave rose empty hills glowing golden in the day’s last light; there was no other sign of human habitation. “My God,” one of the sailors gasped. “Where are we? How far did we drift?”

On an August evening sometime in the mid-1950s, as another perfect Southern California day drew down to darkness, a small sailboat on its way home to the Newport Beach harbor skated too close to shore and found itself trapped in the surf. The sailors were starting to panic when a group of browned and burly men on the shore spotted them and swam out through the black water to help beach the boat. As they landed, the smell of roasting meat wafted over from what looked to be a village of thatched huts set amongst palm trees and tropical growth. On the beach, a group of natives sat around a bonfire, drinking and singing. Behind this cozy enclave rose empty hills glowing golden in the day’s last light; there was no other sign of human habitation. “My God,” one of the sailors gasped. “Where are we? How far did we drift?”

They had strayed just a mile and a half. They’d landed not on some South Pacific island but on the rustic shores of Crystal Cove, California, beloved retreat of vacationing American families. Like many old, perhaps apocryphal, stories about the cove, this one reveals an essential truth about the place: to those who summered there, the life was ideal; to passersby, it seemed impossibly exotic, a tropical fantasia, a mirage. It is a tale from one of California’s golden ages, when automobile motoring had opened up new vistas and beach colonies sprang up along the coast from Malibu to San Diego. A time when it was legal to dive for abalone—and there were still abalone left to dive for. When the hills beyond the beach were thick with coyote bush and toyon and sage.

It’s hard now to recall what Orange County looked like then, when its rolling plains held little besides yellow pastures and orange groves. A drive down the Pacific Coast Highway today reveals mile after mile of housing developments, shopping malls, time-share condos, and golf courses. And yet, remarkably, Crystal Cove—a small settlement of timeworn cottages tucked into an otherwise undeveloped three-mile stretch of beach—remains frozen in time.

There’s a distinct feeling of time travel that accompanies any visit to the cove. The turnoff from Pacific Coast Highway quickly drops down to a one-lane road snaking under towering eucalyptus trees and through embankments overgrown with morning glory. The roar of highway traffic gives way to the slow, rhythmic build and crash of waves. The smell of Old California reaches up from the past: the winelike ferment of warm ice plant and eucalyptus, the velvety dust of crumbling road, and the tang of drying seaweed—all wrapped in a fine mesh of ocean salt. The cottages, too, look much as they ever have, an appealingly haphazard collection of architectural odds and ends nestled in so cozily that they seem to have grown here, twining along the bluffs with the bougainvillea and nasturtiums.

What is this oasis in time, and how did it remain untouched while the rest of the region evolved into a modern suburban landscape? The cove’s origins date back to the early 1920s and an unusual agreement between a powerful landowner and a handful of California families: rancher James Irvine Jr., who owned the cove, allowed people to camp on an unused slip of his vast property and eventually construct simple vacation cabins there, but he retained ownership of the land under them. A naturalist, Irvine preferred to leave much of his land in an untamed state, and through the years not much changed here. But despite its uniqueness and isolation, the cove acted as a microcosm of California history. It was a set for Hollywood filmmakers during the silent-film boom, a drop-off spot for Prohibition-era rumrunners, a destination for motorists during the early auto-touring movement, a staging ground for postwar tiki parties and luaus, and a continual source of inspiration for nearby Laguna’s famed art community. Through it all, however, the place never seemed to change. Without the right to sell or develop the land, the residents—and their houses—were locked in time, and Crystal Cove remained a simple beach colony while nearby coastal development skyrocketed.

With Irvine’s death came a decision about the future of this last remaining undeveloped piece of Orange County coastline. Luckily, his vision prevailed, and in 1979 the Irvine Company sold the cove, and nearly three thousand acres surrounding it, to the California Department of Parks and Recreation for the formation of Crystal Cove State Park. In order to make the cove a true public park accessible to all Californians, the longtime residents eventually moved out. Today the cottages continue to proffer their funky charm as research facilities, educational and interpretive centers, and overnight vacation rentals for park visitors.

Crystal Cove has always been an expression of individuality, so any history of it must celebrate the people who made it a place like no other: its early amateur architects, the activists who worked to protect it, the families who maintained its history over multiple generations, and the larger-than-life personalities who enlivened day-to-day activity on the beach. Though the members of this community are no longer gathered in residence here, their legacy, and their spirit, is palpable. No matter how much the cove changes, in some essential ways it always stays the same; its singular atmosphere is inherent and cannot be lost. If places, like people, can be said to have natural genius, then Crystal Cove is a savant. It is overgrown to perfection, both casual and glamorous, welcoming and discreet—all without ever seeming to try. Park visitors today are still amazed at what they have stumbled upon. They sense what enchanted those rescued sailors, the spirit of this unlikely paradise on the sand.

Buy a copy of Crystal Cove Cottages.

To learn more about the cottages, visit the Crystal Cove Conservancy and the California State Parks Department.